Once, when I worked for the Red Cross in Australia, we asked an advertising agency to help us figure out the level of public interest in HIV/AIDS, one of the main focuses of our international work. The answer came back: somewhere between snake bites and stomach cancer!

I was reminded of that dire reality when I read yet again that jazz music accounts for around 1% of the recorded music market in North America. Just above children’s music and just below classical. In Germany, jazz holds a whopping 1.5% of the market. In Britain, where jazz is enjoying an especially hot renaissance, the genre gets 2% of the loot.

For years I force-fed myself this music. If I was to claim to be a true music nut I had to love Jazz. Loving Jazz was an essential brick in the wall of my credibility. Something that would set me apart from the casual listener and metal head. Jazz was music for smart and cool people. And I definitely wanted those attributes, especially to impress women. A bit of Oscar Peterson or Lionel Hampton in the background as we ‘talked’ was the go-to ritual for the few dates I managed to conjure as an undergrad.

That Jazz was hard to understand was an important part of the blessing it bestowed on listeners. This was something I valued yet really resented. But I was as determined as Jacob in his wrestling match with the Angel, to come out with a win. I knew that if I did get victory over Jazz, I would be able to feel a similar gravitas and intellectuality as I projected onto my classical loving siblings.

I bought lots of CDs. Monk, Miles, Art Blakey, Sonny Rollins, Randy Weston, Bill Holman. They were mostly played when I had other things to do, like finishing a report, or answering emails. Over-egged background music. Finding a groove or melody that struck with me was rare, and other than Underground by Thelonius Monk, I never remembered what a particular CD sounded like the next time I listened. I perceived a block.

But still I persevered.

Putting a bunch of tracks together in a mixtape helped somewhat but only in the way that repeatedly eating a food you don’t like allows you from time to time to chomp on something tasty.

I kept on buying the stuff.

Occasionally, there would come a breakthrough.

In the days before downloading and streaming, I picked up a cheap CD at Melbourne airport of Coltrane’s greatest hits. If there was one guy that I wanted to ‘get’ above all others it was Coltrane. Many hours later I’m sitting in the tiniest of hotel rooms in Geneva checking my emails. My new CD is playing on the tinny laptop speaker. I stop before hitting ‘send’ completely blown away. I’m overcome by what I can only describe as ‘the Spirit’. Coltrane is not playing his sax, his sax is singing, more like shouting or raving, seemingly of its own accord. Coltrane, the blower, is almost irrelevant. Like some djinn released from the confines of a tarnished oil lamp the music grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and said, ‘now, hear this motherfucker.’ The intensity and urgency of the sound was almost visible. Rather, the sound of the music made we perceive my surroundings in a new way. I could see sheets and waves of music all around me. For the first time I wasn’t looking for a hook or a riff or a melody line. I don’t even remember now which track it was, but I felt every note coming out of his saxophone. It was, to steal Keith Jarrett’s description of electric music, ‘vast’.

For the first time ever, I was feeling music.

Sadly, I’ve not felt that intensity again. About 2 years ago I stopped listening to Jazz. The agony of defeat. I had given it the old college try but just did not connect. I grew resentful. Who did Jazz think it was, anyway? So pompous and arrogant and indecipherable. I didn’t want to work that hard. I was also troubled by the unavoidable conclusion: I just wasn’t smart enough to appreciate Jazz.

Over the course of a period from perhaps 1960 to 2000 (to speak in very rough terms), genre became not only the key way to interpret popular music, but one of its most powerful modes of creating a hierarchy of value. From the authenticity – and authority – of rock to the “Disco Sucks” campaign of the 1970s, and from the much-touted “realness” of country music to Wynton Marsalis’s increasingly strange, transphobic comments from the early 1990s on fusion as a kind of musical “cross-dressing,”… Baby Boomers and Generation Xers invested heavily in a discourse of genre purity as a way of attaching value to their chosen object of attention. [Gabriel Solis]

During those self-imposed ‘learning to love Jazz’ years, I bought my CDs in record stores where such music was clearly and boldly (usually in permanent marker) labelled. If there was anything other than Louis Armstrong, the bebop heroes, Wynton Marsalis and an occasional Dixieland collection, my mind didn’t register it. Jazz to me was trad and bebop full stop. This is what JBHifi and Readings filled their Jazz sections with.

Artists that I really liked–George Benson, Mose Allison–seemed to fall into a different category. A hybrid genre of pop, blues and R&B with jazzy overtones. Ernest Ranglin. Great guitarist but more reggae than Jazz. My inclination to gather all these and others (Jimmy McGriff, Big Joe Turner, Ramsey Lewis) together with Sonny Rollins, Lee Morgan and Bill Evans and call them Jazz seemed heretical. My Jazz-loving friends told me so. Benson was a joke. Big Joe was a blues singer and Ramsey Lewis was 70s smooth jazz, which by its very description signalled ‘embarrassment’. Get real mate!

But what about Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone? Somehow, even though they had the critics’ ‘seal of approval’ they all seemed to be just as easily at home in that hybrid genre as in Jazz. And why was Aretha, who made some fabulous Jazz records in the early 60s, dismissed as a mere ‘soul singer’?

Yet these artists, even someone like Fela, seemed to tick all the hallowed boxes of Jazz.

Complex. Tick

Improvised. Tick

Swing. Tick

Fun to listen to. Tick Tick Tick.

That last, was something I found hard to credit McCoy Tyner or Albert Ayler with at all.

Of course, what I was up against was not the music but the labelling and marketing of the music. Jazz was the label given to not just a genre of music but to a supposed philosophy, an historical epoch, and an academic discipline. Jazz had its journals and PhD theses. Bow-tied nerds loved to break it down into bitty little bits and explicate it. Jazz was American Classical Music, goddamit. Take it seriously, boy!

This Brahmanical sniffiness was the source of my resentment. Unlike almost every other type of music I listened to, Jazz came encumbered with expectation, sacrality and politics. Even though I was sympathetic to the politics I begrudged all the trappings that apparently could not be separated from the music. To me it seemed the music was the least important part of Jazz. Jazz was a ginormous project and social force. I just wanted to smile and tap my feet.

Of course, I always loved jazz. It was everywhere. It was in some respects the very foundation, or maybe the glue that held so much of the music I love together. But I had to drop the label and all its associated baggage to come to this point. Who doesn’t like improvised music that swings? I mean, come on! I found jazz in the horn playing of Pakistani wedding band clarinetists, as well as in Carnatic music. It was in all sorts of African music not just rumba and soukous but afrobeat, benga and Highlife. I heard jazz in Patsy Cline’s singing as well as Miriam Makeba’s renditions. Memphis Slim, and Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown played jazz even though I’d have to look in the ‘Blues’ section at record stores. Bob Wills and The Band, Asleep at the Wheel and the Dead played a version of jazz too. And George Benson, Brother Jack McDuff, Lou Donaldson, Trudy Pitts and Chuck Mangione, all those soul jazz cats, were now luminaries, not outcasts.

Disco and funk, hip-hop and country all washed their clothes in jazz and vice versa. What a relief it was to break down the Great Wall of Bebop and mainstream American jazz. There was cool jazz (y) music coming from Poland, the Balkans, Japan, India, Latin America and Lebanon. Listen to some of the soundtracks from Hindi films in the 1950s and you’ll hear jazz there too.

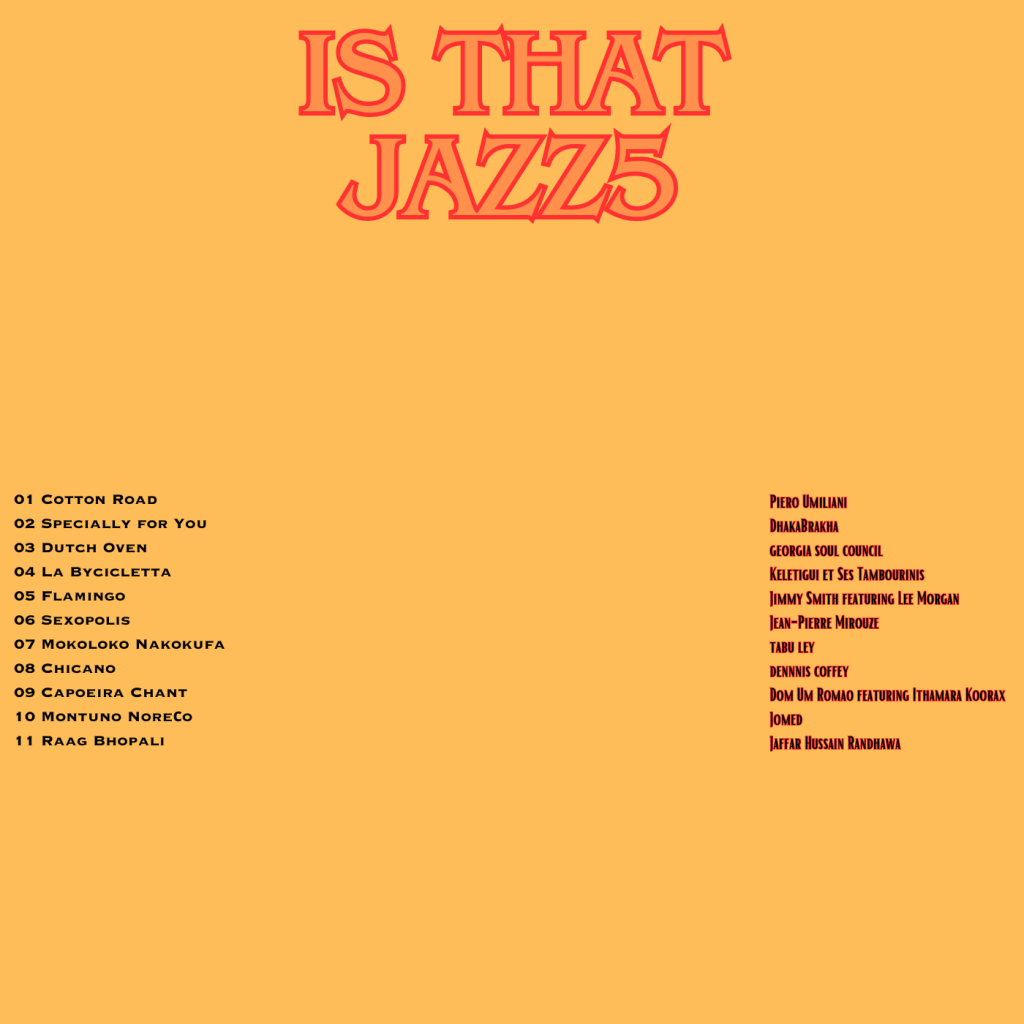

In my various series, “Is This Jazz?”, “Jazzy Vocals” and “Global Jazz” I am trying to capture those exciting, global and surprising sides of this great American enterprise known as jazz.

Here is my latest roll of the dice.

I have to concur Mr SP – it took me a long time to come around to Jazz in it various guises, but it was worth it. Another cracking comp by the way, in a long line of cracking comps.

LikeLike

Thanks Hal. Death to jazz. Long live jazz

LikeLike

Thank you for the mix and also for the commentary. You bring up a ton of

interesting issues, just one of the implications being that the very term “jazz” might

be so abstract or general (attempting to cover so much ground) that it’s by now

become more or less obfuscatory. To be sure, I’ve known my share of jazz snobs, i.e.,

the kinds of folks who would insist that only Subcategory X is REAL jazz, and that all

of the other subcategories, or variants, or kindred forms from further afield, are only

lounge music or fusion or fake jazz or whatever. But I tend to prefer those types of

jazz that I think of as somehow “simpler” — which is not to say simplistic — and this

preference sometimes leads me to choices that the jazz enthusiasts as such might

very well find questionable.

For instance, my idea of a thoroughly, unimpeachably enjoyable jazz tune would

probably be something like Sidney Bechet’s “Blue Horizon,” or Jimmy Giuffre’s “The

Train and the River,” or — and here we go, now — maybe even Woody Herman’s “At

the Woodchopper’s Ball.” And while I very much LIKE the masterworks of John

Coltrane and of Ornette Coleman, I absolutely LOVE such pieces as “Bessie’s Blues”

(from the former) and “Ramblin'” and “Una Muy Bonita” (from the latter) — none of

which are likely to head anyone’s list of the most ambitious or innovative or even

representative examples of jazz. On the other hand, I would also make all the

allowances in the world, almost without exception, for any kind of jazz (Eddie

Lang? Joe Pass? Sonny Sharrock?) which prominently features guitar. So there’s that as well.

Perhaps I’ll be forgiven for seizing this opportunity to recount a little bit of a jazz-related anecdote.

Decades ago, I took a college-level music appreciation course that surveyed

African-American music from blues and gospel to jazz. The instructor was none

other than the celebrated trumpet player and bandleader Bobby Bradford:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobby_Bradford.

Yet the story I’d like to tell comes not actually from my own experience but instead

from the experience of Tony Fernandez (RIP), a friend who’d previously taken the

course and then recommended it to me. Tony was Cuban, and decidedly

Caucasian-complected for a Cuban at that. According to him, when he’d taken the

class, everyone other than himself and this older white woman had been

African-American — the majority apparently consisting of athletes whose coach had

railroaded them into signing up in the first place.

So there was a moment when Bradford was trying to introduce what would once

have been referred to as The Negro Spiritual. After asking for a possible

illustration of the genre, he stood scanning the group from one side to the other,

looking to see who might happen to raise a hand. The athletes individually and

collectively slouched back in silence. All of a sudden, a tremulous, warbling voice

broke out into the refrain from “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” And whose voice was it?

It was, of course, that of the older white woman. Looking directly at Tony — indeed,

fixing him in the eye — Bradford waited just a beat and said, “Folks, we are living in

troubled times!”

LikeLike

Hi Crab Devil. That’s a great story (you have so many)! It leads me y ybĥ about how so much African American music (jazz and blues in particular) has been fetishized and ghettoized by white listeners. And how genre boundaries are solidified to the point that labels like blues and jazz represent primarily only what a group of white critics say it is. A disconnect of African Americans from a part of their culture and heritage while European Americans claim to be the experts.

LikeLike

I concur with your understanding of Jazz. A broad definition rather than rigid and canonical. I just learned of an old book Notes and Tones which I want to get hold of. Apparently interviews with jazz musicians by other musicians in which the likes of Miles etc speak frankly about the term jazz and other subjects not necessarily addressed in other interviews. Have you heard of it?

LikeLike

I’m not familiar with “Notes and Tones,” though it does sound like an interesting read! Your follow-ups are reminding me of some more anecdotes from Bobby Bradford. The guy himself had definitely been around the block. He’d started out (if I recall the particulars correctly) in Texas in the late 1940s, leading a small combo that used to back up whichever famous jazz stars would come through town. I keep thinking, though I could be wrong here, that his band itself had initially been somewhat on the swingy, jump-bluesy side. In any case, he became thoroughly conversant with straight-ahead and bebop-oriented jazz, and he later on developed an approach that was relatively more “free” or “experimental.” So Bradford, for his own part, was very much open-minded about what could, after all, count as fitting into the broader category of “jazz.”

Yet Bradford also emphasized that some of the greatest jazz musicians had been strikingly judgmental about forms which they did not happen to appreciate or enjoy. The most obvious case in point would have been Louis Armstrong. As Bradford told us, Satchmo had disparagingly, if not outright mockingly, said of bebop that it wasn’t jazz at all — it was “Chinese music.” And he had reportedly joked, when a waiter in a club dropped a tray and the glasses went crashing, “Hey! No bebop in here!”

Again, though, I can’t imagine that the subtext would have been for Bradford to impugn let alone denounce (in this case) Louis Armstrong. Instead, I think he meant to emphasize that “jazz” has changed and diversified so much over time that even some of its most noted practitioners have had occasion to disagree over what does or doesn’t belong within the category.

To my mind, what goes for “jazz” also goes for “rock and roll” (in whatever typographical variation one might happen to prefer). Of course, this latter term itself has a long, convoluted, and conflicted history. But my point here would be that even during the 1950s, which everyone thinks of as Rock ‘n’ Roll’s heyday, the phrase was stretched so thin (as if any one description could very helpfully cover everything from “Maybellene” and “Earth Angel” to “Great Balls of Fire” and “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?”) that it must have seemed considerably more evasive than descriptive.

Just a few years ago, I was fortunate to attend a Q&A session featuring the legendary Mike Stoller, who with his partner Jerry Lieber had been part of the team which wrote and produced so many hits — for Big Mama Thornton, for Elvis, for the Coasters and the Drifters, for Peggy Lee, for almost everybody. The event was hosted by the music department at a local community college, and one student asked Mike to comment on the term “Rock ‘n’ Roll,” i.e., from the perspective of a bona fide pioneer who’d been there at the time. Mike explained that he had always, going back to the 1950s, thought of “Rock ‘n’ Roll” as little more than a label which the entertainment industry had adopted in order to facilitate advertising and marketing and the like. So now I wonder how much all of THAT might apply to the term “jazz” as well!

Here, incidentally, is a photo from the event in question. With any luck, you’ll be able to see that Mike happens quite gratifyingly to be wearing a little button that reads “DUMP TRUMP”: https://imgur.com/a/ZC4GZCS .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your thoughts, Crab Devil. Do you remember what Stoller preferred to ‘rock n roll’? I know when I was doing the Box Set last year on ‘country-rock’, I had a hard time drawing the borders of that particular genre. Or was it even a genre. I know some insist that the best way to redefine Jazz is to use BAM [Black American music]. I guess we do need some way to categorise our world and experiences and so that is where labels come in handy. In my own collection I use only very broad genre labels, including “jazz” I must confess. Others I know eschew the whole concept of genre and have their music completely unlabelled.

I like his pin! Which makes me think of another interesting question, does the Donald listen to any music at all? If he does I would say he’s a classic rock sort of guy. (With no disrespect intended to classic rockers or cr fans.)

LikeLike