Once, when I worked for the Red Cross in Australia, we asked an advertising agency to help us figure out the level of public interest in HIV/AIDS, one of the main focuses of our international work. The answer came back: somewhere between snake bites and stomach cancer!

I was reminded of that dire reality when I read yet again that jazz music accounts for around 1% of the recorded music market in North America. Just above children’s music and just below classical. In Germany, jazz holds a whopping 1.5% of the market. In Britain, where jazz is enjoying an especially hot renaissance, the genre gets 2% of the loot.

For years I force-fed myself this music. If I was to claim to be a true music nut I had to love Jazz. Loving Jazz was an essential brick in the wall of my credibility. Something that would set me apart from the casual listener and metal head. Jazz was music for smart and cool people. And I definitely wanted those attributes, especially to impress women. A bit of Oscar Peterson or Lionel Hampton in the background as we ‘talked’ was the go-to ritual for the few dates I managed to conjure as an undergrad.

That Jazz was hard to understand was an important part of the blessing it bestowed on listeners. This was something I valued yet really resented. But I was as determined as Jacob in his wrestling match with the Angel, to come out with a win. I knew that if I did get victory over Jazz, I would be able to feel a similar gravitas and intellectuality as I projected onto my classical loving siblings.

I bought lots of CDs. Monk, Miles, Art Blakey, Sonny Rollins, Randy Weston, Bill Holman. They were mostly played when I had other things to do, like finishing a report, or answering emails. Over-egged background music. Finding a groove or melody that struck with me was rare, and other than Underground by Thelonius Monk, I never remembered what a particular CD sounded like the next time I listened. I perceived a block.

But still I persevered.

Putting a bunch of tracks together in a mixtape helped somewhat but only in the way that repeatedly eating a food you don’t like allows you from time to time to chomp on something tasty.

I kept on buying the stuff.

Occasionally, there would come a breakthrough.

In the days before downloading and streaming, I picked up a cheap CD at Melbourne airport of Coltrane’s greatest hits. If there was one guy that I wanted to ‘get’ above all others it was Coltrane. Many hours later I’m sitting in the tiniest of hotel rooms in Geneva checking my emails. My new CD is playing on the tinny laptop speaker. I stop before hitting ‘send’ completely blown away. I’m overcome by what I can only describe as ‘the Spirit’. Coltrane is not playing his sax, his sax is singing, more like shouting or raving, seemingly of its own accord. Coltrane, the blower, is almost irrelevant. Like some djinn released from the confines of a tarnished oil lamp the music grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and said, ‘now, hear this motherfucker.’ The intensity and urgency of the sound was almost visible. Rather, the sound of the music made we perceive my surroundings in a new way. I could see sheets and waves of music all around me. For the first time I wasn’t looking for a hook or a riff or a melody line. I don’t even remember now which track it was, but I felt every note coming out of his saxophone. It was, to steal Keith Jarrett’s description of electric music, ‘vast’.

For the first time ever, I was feeling music.

Sadly, I’ve not felt that intensity again. About 2 years ago I stopped listening to Jazz. The agony of defeat. I had given it the old college try but just did not connect. I grew resentful. Who did Jazz think it was, anyway? So pompous and arrogant and indecipherable. I didn’t want to work that hard. I was also troubled by the unavoidable conclusion: I just wasn’t smart enough to appreciate Jazz.

Over the course of a period from perhaps 1960 to 2000 (to speak in very rough terms), genre became not only the key way to interpret popular music, but one of its most powerful modes of creating a hierarchy of value. From the authenticity – and authority – of rock to the “Disco Sucks” campaign of the 1970s, and from the much-touted “realness” of country music to Wynton Marsalis’s increasingly strange, transphobic comments from the early 1990s on fusion as a kind of musical “cross-dressing,”… Baby Boomers and Generation Xers invested heavily in a discourse of genre purity as a way of attaching value to their chosen object of attention. [Gabriel Solis]

During those self-imposed ‘learning to love Jazz’ years, I bought my CDs in record stores where such music was clearly and boldly (usually in permanent marker) labelled. If there was anything other than Louis Armstrong, the bebop heroes, Wynton Marsalis and an occasional Dixieland collection, my mind didn’t register it. Jazz to me was trad and bebop full stop. This is what JBHifi and Readings filled their Jazz sections with.

Artists that I really liked–George Benson, Mose Allison–seemed to fall into a different category. A hybrid genre of pop, blues and R&B with jazzy overtones. Ernest Ranglin. Great guitarist but more reggae than Jazz. My inclination to gather all these and others (Jimmy McGriff, Big Joe Turner, Ramsey Lewis) together with Sonny Rollins, Lee Morgan and Bill Evans and call them Jazz seemed heretical. My Jazz-loving friends told me so. Benson was a joke. Big Joe was a blues singer and Ramsey Lewis was 70s smooth jazz, which by its very description signalled ‘embarrassment’. Get real mate!

But what about Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone? Somehow, even though they had the critics’ ‘seal of approval’ they all seemed to be just as easily at home in that hybrid genre as in Jazz. And why was Aretha, who made some fabulous Jazz records in the early 60s, dismissed as a mere ‘soul singer’?

Yet these artists, even someone like Fela, seemed to tick all the hallowed boxes of Jazz.

Complex. Tick

Improvised. Tick

Swing. Tick

Fun to listen to. Tick Tick Tick.

That last, was something I found hard to credit McCoy Tyner or Albert Ayler with at all.

Of course, what I was up against was not the music but the labelling and marketing of the music. Jazz was the label given to not just a genre of music but to a supposed philosophy, an historical epoch, and an academic discipline. Jazz had its journals and PhD theses. Bow-tied nerds loved to break it down into bitty little bits and explicate it. Jazz was American Classical Music, goddamit. Take it seriously, boy!

This Brahmanical sniffiness was the source of my resentment. Unlike almost every other type of music I listened to, Jazz came encumbered with expectation, sacrality and politics. Even though I was sympathetic to the politics I begrudged all the trappings that apparently could not be separated from the music. To me it seemed the music was the least important part of Jazz. Jazz was a ginormous project and social force. I just wanted to smile and tap my feet.

Of course, I always loved jazz. It was everywhere. It was in some respects the very foundation, or maybe the glue that held so much of the music I love together. But I had to drop the label and all its associated baggage to come to this point. Who doesn’t like improvised music that swings? I mean, come on! I found jazz in the horn playing of Pakistani wedding band clarinetists, as well as in Carnatic music. It was in all sorts of African music not just rumba and soukous but afrobeat, benga and Highlife. I heard jazz in Patsy Cline’s singing as well as Miriam Makeba’s renditions. Memphis Slim, and Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown played jazz even though I’d have to look in the ‘Blues’ section at record stores. Bob Wills and The Band, Asleep at the Wheel and the Dead played a version of jazz too. And George Benson, Brother Jack McDuff, Lou Donaldson, Trudy Pitts and Chuck Mangione, all those soul jazz cats, were now luminaries, not outcasts.

Disco and funk, hip-hop and country all washed their clothes in jazz and vice versa. What a relief it was to break down the Great Wall of Bebop and mainstream American jazz. There was cool jazz (y) music coming from Poland, the Balkans, Japan, India, Latin America and Lebanon. Listen to some of the soundtracks from Hindi films in the 1950s and you’ll hear jazz there too.

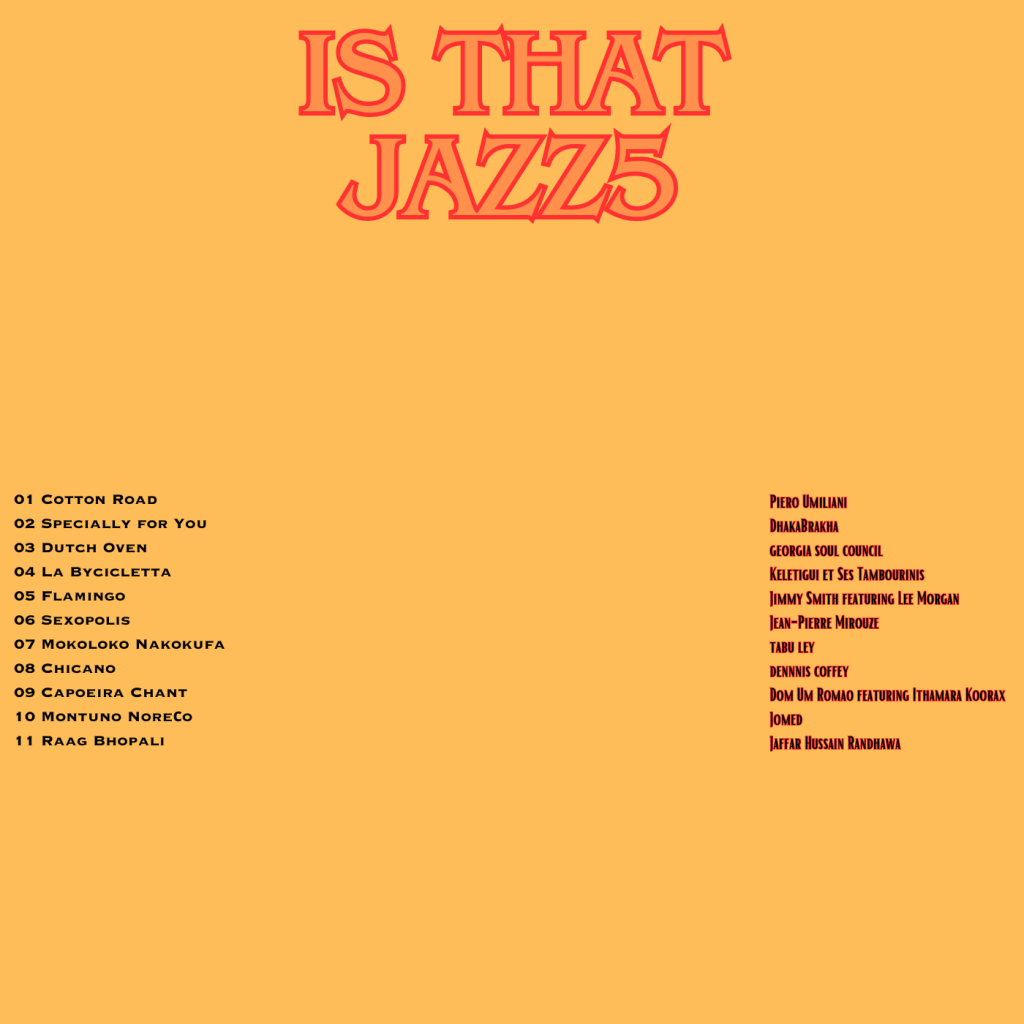

In my various series, “Is This Jazz?”, “Jazzy Vocals” and “Global Jazz” I am trying to capture those exciting, global and surprising sides of this great American enterprise known as jazz.

Here is my latest roll of the dice.